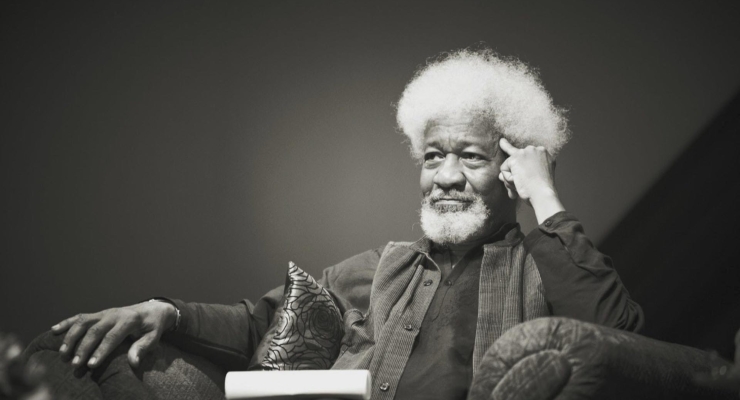

Wole Soyinka and the Question of Power, Law, and the Politics of Visas

By Legal Africa Editorial Team

When Nigerian Nobel laureate Prof. Wole Soyinka revealed that his U.S. visa had been revoked by the Trump administration, it stirred a wave of reflection far beyond literature and politics. The incident rooted in a short, polite letter from the U.S. Consulate in Lagos has evolved into a conversation on law, discretion, and the fragility of mobility in a politically charged world.

According to Al Jazeera, Soyinka disclosed that the letter, dated October 23, 2025, was delivered to him by the U.S. Department of State. It requested that he “present his passport for physical cancellation” because “additional information became available after the visa was issued.” The message was short, bureaucratic, and deeply symbolic.

“I have no visa. I am banned. I am very content,” Soyinka said during a reading session in Lagos words filled with the calm defiance that has long defined him.

The U.S. Embassy declined to comment, citing policy restrictions against discussing individual visa matters. Yet, the timing and tone of the revocation left many observers questioning whether the decision was a routine security matter or a subtle political rebuke.

A Lawful Act, a Loaded Gesture

Under U.S. immigration law, the revocation of a visa is not unlawful. Section 221(i) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) grants the Secretary of State broad discretion to revoke a visa “at any time.” This means that no explanation is required and no formal appeal process exists. In legal terms, this is known as the doctrine of consular non-reviewability the principle that visa decisions by consular officers are beyond judicial scrutiny.

From a purely legal standpoint, Soyinka’s visa revocation is therefore well within U.S. law. But law, as Soyinka himself has often argued, is never divorced from power and politics. The discretionary nature of the act invites scrutiny into the why, not just the how.

Free Speech and Political Backlash

In his statement to the press, Soyinka hinted that his criticism of Donald Trump might have provoked the move. The Al Jazeera report recalls his earlier remarks comparing Trump to Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, calling him “a political barbarian with the instincts of a despot.”

If the revocation was indeed linked to his past criticisms, it introduces a profound legal irony: a state exercising a lawful right in a way that punishes lawful speech.

In the U.S., the First Amendment protects free expression but only for those within U.S. jurisdiction. For a foreign national like Soyinka, there is no constitutional safeguard against a visa being withdrawn in retaliation for speech. It exposes a blind spot in global justice where the reach of power extends beyond the borders of law.

The Soft Power Implications

Wole Soyinka is not an ordinary traveller. He is Africa’s first Nobel Laureate in Literature, a global voice against tyranny, and a symbol of intellectual freedom. When a nation revokes his visa, it sends a message that travels faster than any aircraft.

Diplomatically, it raises questions about how states use immigration law as a tool of soft power — rewarding allies and silencing critics without ever saying so. The act may be legal, but it is also performative: a quiet declaration that access is conditional on compliance.

For Africa, this serves as a moment of reflection. How do our states treat visiting intellectuals, dissidents, or critics? Are we transparent and fair when we control the entry and exit of others? The sovereignty of visas cuts both ways and justice demands consistency.

A Case Study in Legal Discretion

From a legal education standpoint, Soyinka’s experience provides a case study in administrative discretion and its limits. The following legal principles are at play:

-

Consular Non-Reviewability:

U.S. courts traditionally avoid interfering in visa decisions. This doctrine ensures that visa revocations remain outside judicial oversight effectively giving consular officers unchecked power. -

Due Process and Foreign Nationals:

Non-citizens outside U.S. soil are not entitled to constitutional protections under due process. Therefore, revocation letters like Soyinka’s require neither justification nor explanation. -

Political Neutrality and Foreign Policy Law:

Visa law operates within the broader sphere of U.S. foreign policy, where political considerations often shape administrative decisions.

In this light, the Soyinka case may be legally unimpeachable but ethically and diplomatically questionable.

Africa’s Legal Mirror

For African lawyers, policymakers, and scholars, the Soyinka episode offers a valuable reflection point. It reveals how mobility rights intersect with political expression, and how foreign states sometimes exercise power over African voices without accountability.

African countries can learn from this by strengthening their own visa governance frameworks, ensuring transparency, accountability, and recourse mechanisms for foreign scholars and professionals. Justice, after all, must not only be done but be seen to be done whether in Washington or Abuja.

Soyinka’s Response: The Last Word

As always, Soyinka met the situation with poetry rather than protest. “I am very content,” he said, “The world is vast enough.” His calm is not surrender it is resistance shaped by wisdom. It reminds us that while states may control borders, they cannot confine the freedom of thought.

Conclusion: Law Beyond Borders

The revocation of Wole Soyinka’s visa is more than an administrative act it is a collision of law, politics, and human dignity. It underscores how the most powerful legal tools often operate in silence, under the cloak of discretion.

For Legal Africa, this moment demands not outrage but reflection.

When legality and morality diverge, which should prevail?

And when borders close around truth, who will still speak?